The ‘Afghan Man You Need To Know’ Works for HIAS Partner in Pittsburgh

By Dan Friedman, HIAS.org

Apr 19, 2022

Zubair shows me his Pittsburgh Steelers cap.

“I like sports! I watched the Super Bowl in Afghanistan,” he says, “and I heard all about the Steelers from a commander at Fort McCoy who was from Pittsburgh.”

Knowing of the Steelers, though, did not prepare him for the mania that grips Pittsburgh on game days. I asked how he liked the city, “The weather is similar to Kabul, so we are not worried about cold weather but food, culture, customs are difficult to get used to — and there are too many hills and bridges, it makes it hard for driving!”

As the native reporter for the U.S. Army publication Stars and Stripes – fluent in Dari, Pashto, Urdu and English – the 40-year-old Zubair’s job was to have his finger on Afghanistan’s pulse. On a Zoom call from Pittsburgh, where he now works for HIAS affiliate, Jewish Family and Community Services, Zubair told me, “In the few days up to fall of Kabul, I was doing phone interviews with India and Pakistan, telling them that the ASF [Afghan Special Forces] would be able to hold out.”

Three days before the fall of Kabul on August 15, though, things had changed. He told his colleague J.P. Lawrence “the wind is blowing now, something is happening — you should leave.” Lawrence and his other American colleagues left for the embassy the next day and were evacuated.

Meanwhile there was no plan to extract Zubair who was waiting for the Special Immigrant Visas he had applied for in 2015. The SIV program is an immigration program that grants permanent residence to people who aided the U.S. government abroad. Afghan applicants faced a lengthy wait and, once the Embassy began destroying documents on August 13, it was clear that Zubair’s visa would never arrive.

Zubair described the following 10 days trying to escape a Taliban-ruled Kabul with typical understatement as “really, really hard.” Around the airport, the streets were packed so tight that you couldn’t approach the checkpoints – Zubair got a bloody nose trying. Friends and colleagues hadn’t abandoned him as he tried to get his young family out of a city where he would surely be killed as a collaborator if he stayed. He, his wife and his children aged 12, 10 and 6 slept with their shoes on in case they needed to leave immediately.

Looking back seven months, as his children attend Pittsburgh public schools and he works for JFCS Pittsburgh as a Cultural Navigator, the escape seems surreal. The Stars and Stripes team and friends in America kept trying to get Zubair and family evacuated. After multiple failed attempts, the fact that his boss had been a U.S.A.F. colonel — and was on Zubair’s cell phone — was the decisive factor in finally persuading a soldier at the airport to get them to a plane.

One of the journalist friends trying to help him was Carmen Gentile who wrote a moving story about Zubair’s struggles to escape Taliban-occupied Kabul – “The Afghan man you need to know.” Gentile was also a major mover in setting up a Team Zubair GoFundMe that was so successful in raising money to help Zubair that it morphed into the Afghan Humanitarian Support Alliance helping all arriving Afghan families. Zubair is a remarkable, charismatic person with excellent language skills, a network of American friends and a long record of working for the U.S. army. If the Zubair family could not make a go of it, what chance would other Afghan families have?

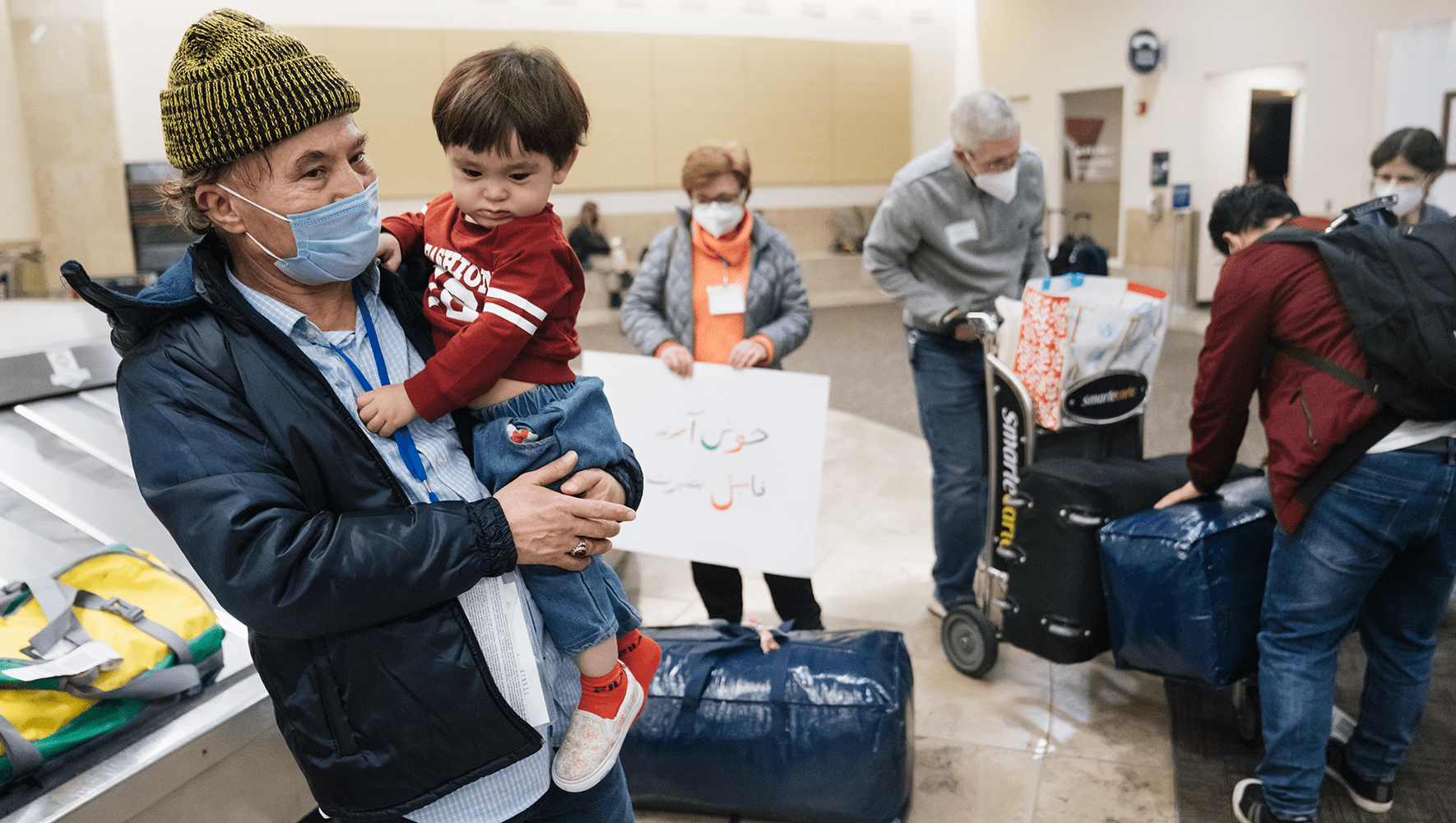

After being flown out of Kabul on the floor of a military plane bound for Qatar, the Zubair family made their way to Wisconsin where they stayed at Fort McCoy for two and a half months for vaccines and documentation. Finally, in November they made it to temporary accommodation in Pittsburgh with a number of other Afghans. Zubair was able to translate for other arrivals and because, after a decade of working for Stars and Stripes, he was familiar with American culture, he was an ideal person to act as a cultural navigator for other families.

Soon JFCS realized that Zubair’s unique abilities to connect should be used on a more strategic level. “I met Zubair via email while he was waiting at Fort McCoy to be resettled in Pittsburgh. From the email exchanges, I learned that Zubair quickly made himself available to help other families at the base to communicate with staff and solve issues such as access to cellphones and obtaining information about the status of their resettlement process,” explained Director of JFCS Refugee & Immigrant Services Ivonne Smith-Tapia. “Very soon after arrival, Zubair became a leader who was able to gather people easily. He leads with kindness and humor. He is aware of his privilege and makes sure other families with less resources and connections in the U.S. have access to resources. For us at JFCS, it is a privilege to have Zubair on our team to help us serve and guide other Afghan refugees in Pittsburgh.”

Growing up in Pakistan during the Russian occupation meant that Zubair could forge good links with that community as well as with Afghans, journalists, resettlement partners and army folk that were already arrayed to help. Instead of finding a single sofa for a family moving into a house, he could help a community find furniture from a set of networks, instead of explaining family by family how to do the laundry, find bus passes or use vending machines, he can run cultural orientation seminars about cultural norms and public behavior in America for the newly arrived.

Zubair’s children are settled and getting used to studying in English. It’s more of a challenge for his wife Fatima, but he’s confident she will find her place in Pittsburgh. He has just got a car so he can be independent at work so the next step is to buy a house so that the family can get properly settled.

“I’ve always had a house for myself. In Afghanistan I built a house for myself.”

It’s a splintered life, though. Many Americans forget that in most cultures people live in extended families, not in the nuclear families presented in domestic sitcoms. Cousins are like siblings, grandparents are constant carers, aunts and uncles are a daily feature of life. Back in Afghanistan the big family house was the center of life, and Zubair still has many family members over there. Communication is possible, but — as we have all found during the pandemic — the wedge of distance is painful. Zubair noticed that, “When we FaceTime with [family in Afghanistan] my younger daughter is very sad because she misses her cousin.”

Though sad to be apart from family and worried for his country, Zubair is putting down his Pittsburgh roots, “people are friendly here, we’re not moving elsewhere, we’re here for a while.” He even has a favorite Steelers moment already!

“I have a happy memory from when we arrived. Our first day in Pittsburgh was November 13. The day after there was a Steelers game against Detroit – it was the first time they had tied [in recent memory]. We were able to go to Mount Washington, me and kids — and we were able to look down and watch the stadium in peace and excitement."