The Sidewalk School: An Education for Those “Without”

By Sharon Samber, HIAS.org

Oct 22, 2020

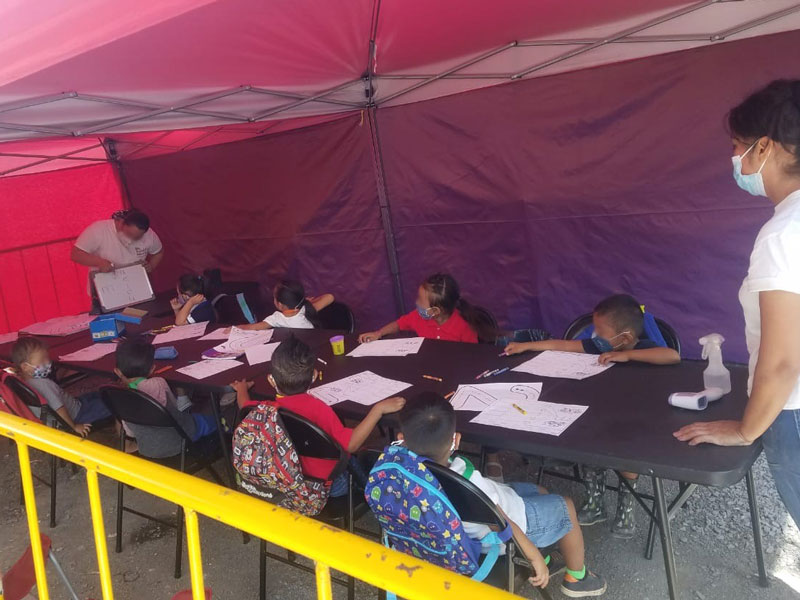

With computer tablets in their hands the children are ready for their online school, but their homes are tents and some have not taken a class for more than a year.

The students of this school, the Sidewalk School, are all asylum-seeking children living in or near an encampment in Matamoros, Mexico, while they wait for their cases to wind through U.S. immigration courts. Many have been in Mexico for months because of the Migrant Protection Protocols, the U.S. policy that allows border officers to refuse non-Mexican asylum seekers entry into the country while their claims are adjudicated. As their families wait in dangerous conditions with no permanent shelter, education has fallen by the wayside.

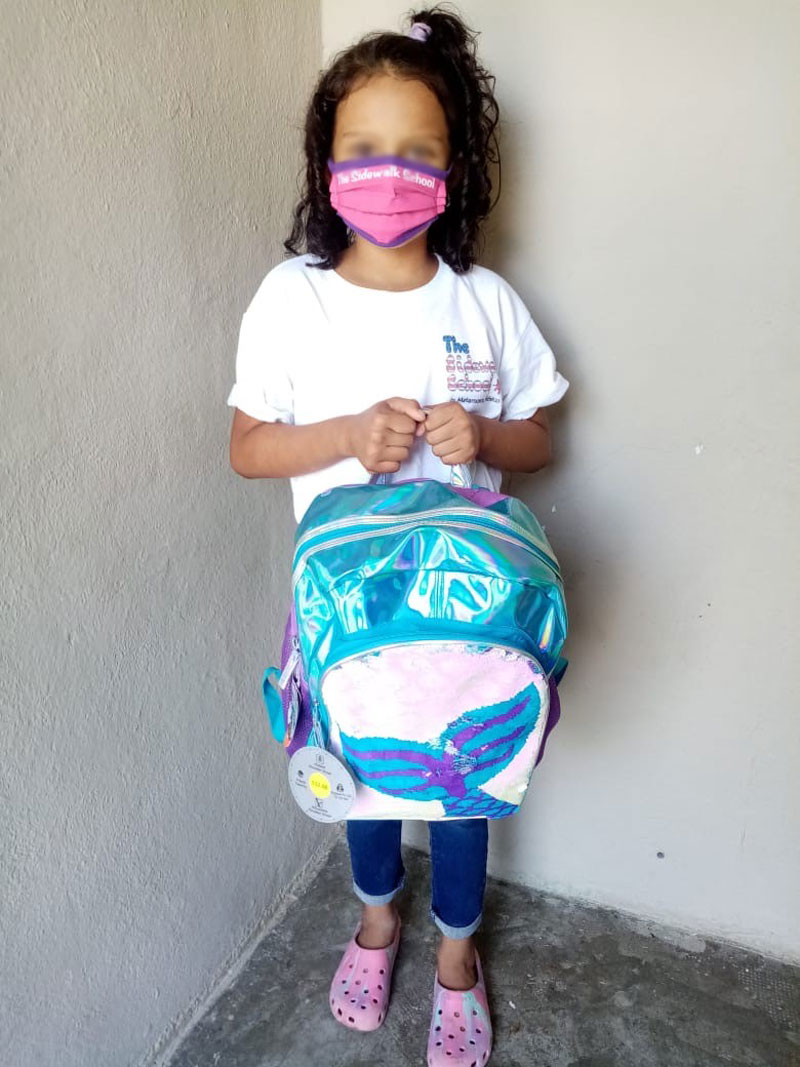

Gaps in education can be difficult to overcome, but the Sidewalk School offers a bit of hope. About 200 children living in Matamoros can now take free weekday classes in math, English, and science. The school also provides general assistance — masks to stop the spread of COVID-19, meals, clothing, blankets, and even some community-building activities.

Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, the school’s director, helped found the Sidewalk School when she heard about people sleeping in boxes at the border. She immediately thought of the children who would be cut off from going to any kind of classes and decided to organize a place where children could come to study and do arts and crafts. The school, which originally was on a literal sidewalk, has operated since last school year began and all the teachers are asylum seekers themselves.

“The goal is to get education where there isn’t any,” said Rangel-Samponaro. “I just wanted all the shelters that want to do something with education to be able to.”

HIAS Border Fellow Nico Palazzo has been trying to help spread the word about the organization and get people to donate computer tablets. With his work as a staff attorney at Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center often hampered because of Trump administration policies, Palazzo says he feels handcuffed in terms of helping people. “Education is the new realm we’re going into,” he mused. “At least I’m doing something good.”

Rocio Melendez Dominguez, HIAS Mexico’s managing attorney, also helped Rangel-Samponaro visit two shelters in Ciudad Juárez. She also shared information on Matamoros, and Rangel-Samponaro will meet with the HIAS team in Matamoros at the end of the month.

After operating in Matamoros for about a year, Rangel-Samponaro has two schools opening in Ciudad Juárez and is considering expanding to Nogales next year.

The school gets some support from foundations and private donations, and it started a GoFundMe page. Rangel-Samponaro, who often pays for school supplies out of her own pocket, is working on getting the school 501(c)3 status.

The mission of the school is “to provide quality education to those who would go without” and Rangel-Samponaro seems intent on doing just that, regardless of continued financial, logistical, or other challenges. She sees the need as something to simply be met.

“Children were not getting any sort of education,” Rangel-Samponaro recalled. “And no one was reaching out to them.”